Peter Hornsby and Ian Newman

Department of Computer Science

Loughborough University,

Loughborough,

Leicestershire, UK

p.m.hornsby@lboro.ac.uk

Abstract

Producing software from predefined components can lead to significant cost savings, together with increases in the reliability of the software. During the software development process, the developers understanding of the nature of the problem changes as possible solutions are explored. As a result, the way in which components are described needs to encompass information from both the problem and the solution domains. The paper describes an approach to component based programming which uses information already generated during the design process to describe components for retrieval. This approach has been implemented in a tool called DesignMatcher, which is being used to explore the validity of the approach.

1. Introduction

Software development within the component paradigm is largely a process of assembling components with no or minor modifications to achieve the desired functionality. Indeed, some software development tools already use a process of visually manipulating components in order to generate working code. Although a range of technologies exists which may be used to support component-based programming from the technical perspective, one of the most significant problems remains: when and how can components be retrieved for reuse. Reuse already takes place informally, as developers reuse both solution strategies and code from personal experience. One of the most effective sources of reuse is other developers who may have addressed similar problems (Greenbaum and Kyng, 1991). However, if formal retrieval systems are used, developers are limited by human memory and other cognitive constraints. The developer must understand what components are available, how to retrieve them, and how the components may be used in order for component-based development to take place. Ultimately, reuse relies on the developers experience and understanding of possible opportunities for reuse. Graham (1991) for instance, suggests that it takes a developer a day to learn about a class in any detail.

Unfortunately, many of the existing approaches to retrieval for component based development have significant overheads for the developer. Describing components in formal ways limits their accessibility to those who can use the same notation for retrieval, and (as with any information retrieval problem) essentially requires the classifier and the retriever to have similar views about what a component may be used for. Where components are formally classified for retrieval, information about the context within which the component has been used may be lost, to the detriment of future reuse opportunities. Formal descriptions of components are also based on a fairly rigid view of the development process. However, this process is much less structured than is implied by formal models of the process. Developers address design problems in an opportunistic manner, identifying partial solutions and only using a top-down strategy where the problem is well-structured and the designer already knows a possible decomposition (Guindon, 1990). The understanding of the problem develops in parallel with the development of a solution (Schon, 1983). To put it another way, the requirements stage of development can help the developer to identify possible opportunities for reuse, but if only formal retrieval systems are available, the developer must rely on personal experience, rather than using a retrieval tool which may require a formal description. The Unified Modelling Language (UML) may be used to describe a design as it develops from a real-world problem (using language from the problem domain) through to an implementation (using more technical, solution-centred terms). Consequently, it can capture the developers understanding of the problem from the early stages when the problem is likely to be poorly defined, through to the implemented solution to the problem.

This paper contends that this can be used to provide automated indexing and retrieval tools to support component development without necessitating significant additional work by the developer. A research tool called DesignMatcher is outlined which demonstrates how this might be done.

2. Effective component reuse

Electrical engineering catalogues may describe a component across a range of dimensions, such as tolerance, resistance and physical dimensions. A single mode of representation for components cannot identify an individual software component in such a way as to define it for all possible uses. Each time a component is used, there is a wealth of information which may be used to describe the component. In a design described using UML, this information may come from:

- code comments

- requirements documents

- use case models

- class descriptions

- sequence diagrams

This information covers the capabilities of the component, the problem it is being used to address, the components with which it is interacting, and so on. As with other engineering disciplines, software engineering has a number of well known and well understood solutions to many technical problems that can be reused. However, the nature of information makes the nature of components in software engineering sufficiently different to other engineering disciplines to require alternative means of descriptions. Effective component reuse requires an approach to retrieval that has been initialised with components and the additional information required for their retrieval, as well as developers who are able to make use of the retrieval facilities. In both cases, minimising the additional workload for developers is desirable. This suggests that automated approaches to adding components to a component store are likely to meet with more success than approaches which require significant extra effort by developers. Retrieval techniques which depend upon the developers using formal or semiformal descriptions of components are unlikely to be successful since the process of creating a formal description may remove useful information, as well as introducing discrepancies resulting from the different perspectives of the classifier and retriever. Developers may use a sub-optimal component if it saves a significant amount of time; if the developer is already aware of this component before development begins in earnest, they may well adapt the design to incorporate it. Just as a developer must adapt to the implementation language, target system(s) and user population, so they may choose to adapt to an existing component rather than implementing a more optimal solution which takes significantly longer to implement. There are generally many ways to solve a particular problem, and It is up to the developer to decide which is more appropriate (if any) for the problem. There may be no ‘right’ solution. So rather than attempt to establish a mapping between a particular component and a particular problem, and then to say that component x solves problem y, an alternative approach would be to capture the information that describes the problem, and then to use this in order to reuse the solution. By capturing many uses for a component over time, a ‘rich picture’ of how that component can be used may be built up. What the component is called, and how it is described, is dependant upon the person who created the component. But by capturing information about how the component is used in a range of situations, the likelihood that subsequent users can retrieve the component to make use of it increases.

A number of desirable attributes for a component retrieval system exist. These are:

- to be capable of describing components in a number of different ways

- to capture contextual knowledge which can assist the developer in deciding when and how to use the component

- to adapt to the software engineering process as experienced by developers rather than the process as documented

- to minimise the effort required by the developer to store and retrieve components

3. The DesignMatcher tool

A tool has been developed to explore the practical possibilities of this approach. DesignMatcher (DM) is a software development tool that stores designs and code for automatic retrieval in subsequent developments. It uses design materials written in UML, and code written in Java, to provide a mapping from the problem domain to the solution. This enables developers to see how design issues identified in an evolving design have been addressed in previous designs, and to retrieve components and designs for reuse. DM does this in a way which is designed to minimise the developers workload. This section outlines the architecture of DM and then presents a case study which illustrates one possible style of use for DM.

3.1. DesignMatcher: architecture

During the development process, DM reads the design file, and uses this to evaluate existing designs against the developing design. DM can then ‘score’ existing designs and return these scores, together with information about the nature of the match found, to the developer who may then choose to examine the matches in greater detail. In this way the effort required from the developer is minimised, while at the same time aiming to provide the developer with as much useful information about existing components as possible. DM currently operates using Java (code) and Rational Rose (UML design) files as the primary data sources. It is designed to operate in the background of the development process, alerting the developer only when a significant probability of a component match has been found.

Figure 1: DesignMatcher architecture

The architecture of the DM system is illustrated in Figure 1. DM identifies when a file update takes place, and sends a copy of the file to the DM pre-processor. This translates the UML file into a standard format which is passed to the DM matching utility. This applies a series of matching algorithms to the design, which compare it to designs held in the design store. Matching within DM is string based. This is currently the most effective technique since the majority of the useful descriptive information about a component is stored in textual format. For elements such as class names, which are typically written using camel notation, the element is split up into the individual words, so ‘HelloWorld’ becomes ‘Hello World’. This enables more accurate matching to occur as the descriptive terms for the element are identified. Investigations are currently under way to examine the viability of matching routines based on structure, so for example sequence diagrams can be compared to obtain more contextual information about components. The long-term benefits of this are likely to be more accurate identification of similar designs or code, but this will become a more serious issue when the number of designs held in DM rank in the hundreds rather than the tens.

Once one or more matches have been found, details of the matches are returned to the DM client. For each match found, the client displays a brief description of the match, together with an (optional) success rating. The description identifies the name of the matched design, the area of the design within which the match was found, and the phrase which matched the existing and ongoing design. The developer may then obtain more detailed information about each match of interest. They may then choose to retrieve the design from which the match was found, or (if available) the associated code implementation. This can be used by the developer to identify how to perform a particular task, or can provide the developer with code that can be used to implement particular functionality.

4. DesignMatcher: Case Study

This case study describes part of a retrieval process in the context of an existing system development. The process has been applied to a UML file (generated with Rational Rose), although the same principles can be applied to Java class files.

Once a statement of requirements has been produced, the developer uses a UML modelling tool such as Rational Rose to flesh out the analysis and design of the problem. Initially, actors and use cases are defined, together with a short description. This identifies the basic functionality of the system and the entities with which the system will interact.

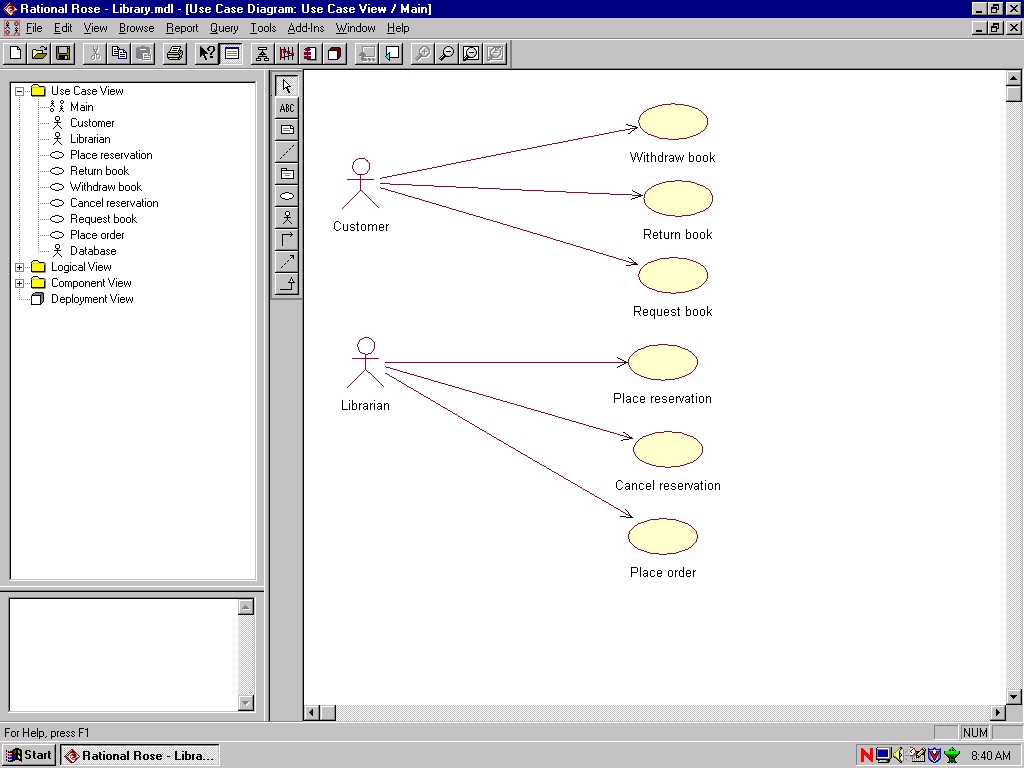

Figure 2: Use case diagram for library management system

Figure 2 illustrates use cases and actors associated with the design of a library management system. This is the design upon which DM will perform the analysis. The user has told DM the name of the operating file, which is read whenever its timestamp is updated. This is then sent to a holding area on the DM server. A DM process running on the server identifies that a new or updated file has been added, and performs evaluation processing on the file. This translates the file into a standard format, and performs matching routines which compare the current design to designs already stored in the DM database. If the results score past a user-defined threshold, the user is alerted that a match has been found.

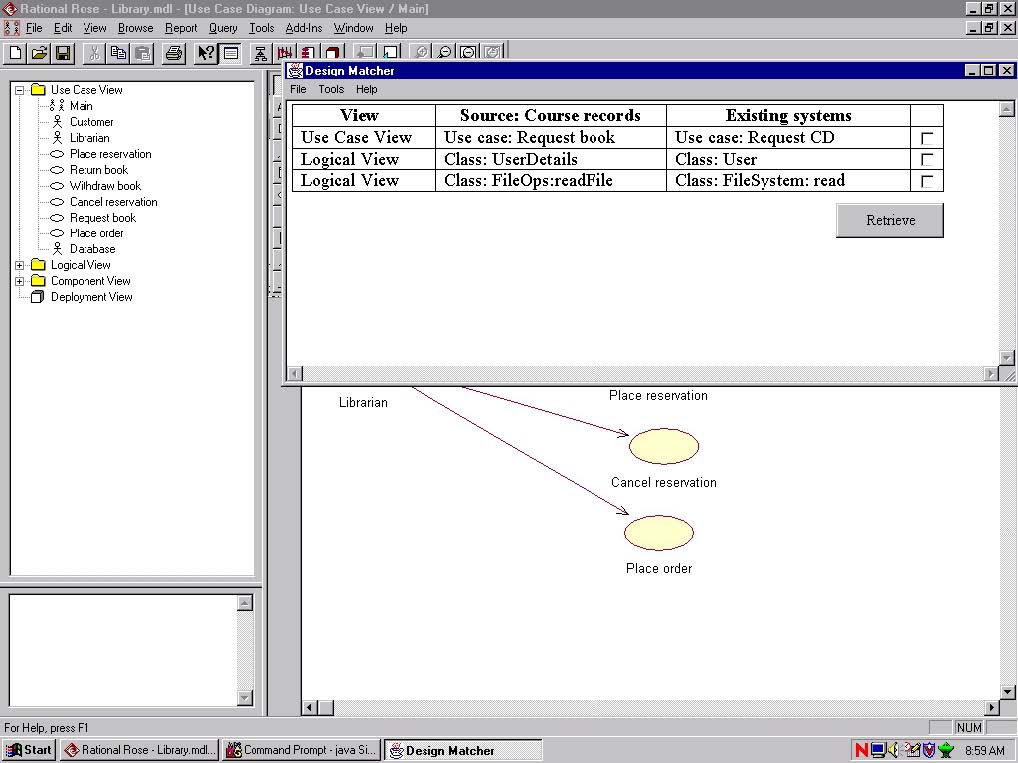

Figure 3: Sample DM interface dialogue results

Once analysis has been performed by DM, the results are returned to the developer. More detailed information can then be obtained about nature of the match, and, if desired, the relevant file retrieved. The developer can also be informed whether or not there is a code implementation of the component. Depending on the similarity of the match, the developer may choose to retrieve and modify an existing system rather than generate one from scratch. In this way, significant development effort can be saved by reusing significant portions of existing systems.

Once the system has been developed, the completed design (with or without implementing code) can be added to DM for future reference. This ‘addition’ process is almost identical to the evaluation process, except that the design and code are added to the DM database with the users details.

5. Discussion

Is the concept of capturing and using this sort of information applicable to software development? Walther and Kolbe (2000) describe a theorem-proving assistant which proves theorems by mathematical induction with the aid of a human advisor. This reuses proofs of previously verified formulae, much as DM reuses aspects of previous designs. Human involvement is required, but only after the system notifies the user of a match. The nature of software development is such that developers are best assisted by tools which operate, as far as possible, in the background. Once a developer has set up the desired matching strategy, they are free to continue working, knowing that they will be alerted when a match for the ongoing development has been found.

Software development is a fluid process, using problem descriptions at a range of levels of abstraction and which incorporates knowledge from the target problem domain. It is proposed that the design information gathered as part of the design process should be captured as an aid to ensuring both easier retrieval and a higher probability of compatibility between retrieved components and the new design. By enforcing no limitation on the number of descriptions which may be associated with any component, DM aims to capture more aspects of each component known to the system and in doing so, to increase the likelihood of success of each component search.

DesignMatcher is still under development, although early results are promising. More powerful matching strategies are expected to be identified as the number of designs and code comments in the system increase. One of the most interesting areas under investigation is the relationship between increased formality and retrieval success. For example, some software companies produce structured UML documentation such as flow of events descriptions. These could be used by DesignMatcher in the earliest stages of development in order to identify opportunities for reuse in the earliest stages of development. Such structured documentation may also be found in code documentation, and this too may add additional information to the matching process.

Another area of interest is the potential for collaboration between groups of developers. When developers are working on the same project, or for the same customers, the language used to describe a problem tends to homogenise – necessarily so, since the different groups must communicate effectively. It would be interesting to see how functionally similar products developed in different problem domains differ, both in the language used to describe the problem and the aspects of the problem considered significant. In theory, the top-level descriptions would be different, but the closer the system got to implementation, and the more similar the components became, the greater the likelihood would be of a match between implementing components.

A tool such as DesignMatcher can facilitate the construction of component libraries by identifying designs and code which address the same type of problem, and generalising from these identified solutions. A similar strategy at a higher level of abstraction could be used to identify reasonable design patterns by looking for common relationships between components. Finally, DesignMatcher can provide an ‘organisational memory’, which could be used to maintain a store of solutions as well as a means of easily accessing design materials for maintenance.

6. Conclusion

Software developers are under increasing pressures to produce reliable, usable software more effectively. Reuse has the potential to significantly benefit the development process, but many approaches to component reuse can significantly add to the developers workload and do not take into account the realities of the development environment or process. DesignMatcher represents a novel approach to retrieval during the development process which better reflects the realities of software developments. It requires minimal effort form developers to add designs and components and offers suggestions for reuse at very low cost during the design and development process.

7. References

Fowler, M., 1999, UML Distilled, Graham, I., 1991, Object-Oriented Methods. Harlow:Addison-Wesley.

Graham, I., 1991, Object-Oriented Methods. Wokingham: Addison-Wesley.

Greenbaum, J., and Kyng, M., 1991, Design at work: Cooperative design of computer systems. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., Hillsdale, NJ.

Guindon, R., 1990, Designing the design process: exploiting opportunistic thoughts. In: Human-Computer Interaction, 5, pp.305-344.

Schon, D.A., 1983, The Reflective Practitioner: how professionals think in action. London: Temple Smith.

Walther, C. and Kolbe, T., 2000, Proving theorems by reuse. In: Artificial Intelligence, 116, 17-66.